Since January 1, 2023, the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG) has been in force in Germany. It is intended to enforce human rights and environmental standards. The EU Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) will come into force shortly. Moreover, there are further initiatives in the EU that entail new reporting and information obligations. Besides its positive effects on social and environmental issues, the CSDDD is likely to have an impact on costs and administrative burden, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and businesses in developing countries.

First step LkSG: Comprehensive evidence required

The German LkSG obliges companies to continuously prove that all suppliers comply with a wide range of international standards in the areas of human rights, social affairs and the environment. In addition to the obligation to end violations within their own company and with direct suppliers, companies should prevent risks in their entire supply chains. This results in extensive tasks such as setting up a risk management system and a grievance mechanism. The measures must be documented annually. Violations can result in severe penalties. In order to support companies in implementing their due diligence obligations, the Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA) develops and publishes handouts. Handouts on risk analysis, appropriateness and complaint procedures have already been published and are available for download on the BAFA homepage.

Documentation obligation passed on to suppliers

The LkSG is initially limited to companies in Germany with 3,000 or more employees, and from 2024 from 1,000 employees. Larger companies have to request information from their suppliers for their own verification. The transfer of due diligence and documentation obligations to SMEs is therefore inevitable. Measured against their size, SMEs require an immense amount of documentation and verification. This can hardly be managed with on-board resources. Additional skilled workers are expensive and scarce. Those who want to escape the bureaucracy are threatened with the loss of orders from large customers.

EU plans: a challange for competitiveness

The planned EU Supply Chain Directive goes one step further: it is intended to include companies with as few as 250 employees in their obligations. The highly complex set of rules is to be transposed into national law by 2025. In the future, companies operating in the internal market will have to comply with 27 different legislations.From the point of view of small and medium-sized enterprises, the new law strengthens one thing above all: internal bureaucracy. Many companies see their international competitiveness threatened.

EP Legal Affairs Committee approves draft report

On 25 April 2023, the Legal Affairs Committee of the EU Parliament adopted the draft report by Dutch Social Democrat Lara Wolters on the EU Supply Chain Directive (Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, CSDDD). Although there have been various changes, the concerns of the economy have still been poorly taken into account. The vote was taken by a large majority. The plenary vote is scheduled for June.

The draft text now available gives rise to fears of serious competitive disadvantages for small and medium-sized enterprises. The draft includes civil liability, extension to SMEs and to the entire value chain, including downstream stages. This means considerable additional work for practically all companies – and legal disputes that are difficult to assess. In particular, there is a risk of disadvantages, especially for those who should be better off by the law: people in developing countries.

Important changes at a glance:

Challange for SMEs

One bra – 1,000 suppliers!

Even simpler bra models are composed of 20+ components. More complex models can contain up to 50 components. If you include not only direct suppliers, but also their upstream suppliers, you quickly get +1,000 suppliers for an article that need to be checked. Supply chains are also changing. Even in the case of random samples according to risk assessment (= not comprehensive), this means an immense additional effort per article. This makes it particularly expensive for smaller series and innovative lines. Large players with simple mass-produced goods have a clear competitive and cost advantage.

Economic pitfalls in the EU and developing countries

The CSDDD causes bureaucratic costs in the EU, which disproportionately affect small and medium-sized enterprises. It is also likely to have a negative impact on suppliers in developing countries – even if there are no violations of human rights or environmental and social standards there. While bureaucracy, certification costs and consultants’ fees are putting a strain on margins in Europe, companies in poorer countries have to fear for orders.

Due to the risk of liability, EU companies are likely to increasingly withdraw from developing countries. There is no integration into world trade that promotes development. This is likely to have a negative impact on per capita incomes in the world’s poorest countries. In addition, the directive weakens the international competitive position vis-à-vis competitors from countries without a comparable regulation.

What is careful enough?

So far, it has not been possible to achieve clarity about the depth of due diligence. In many cases, unclear and open regulations are likely to lead to excessive demands. In contrast to the LkSG, the due diligence obligations are potentially also applicable to indirect business relationships. Calls to limit the obligations to Tier-1 business partners were rejected by all political groups.

With regard to the scope of the due diligence obligations, the European proposal is based on the obligations of the LkSG. It is positive that companies are explicitly allowed to weigh in relation to the contribution to causation, probability of occurrence of damage and extent of damage. In addition, it was clarified that Member States may not go beyond the core content of the Directive in their national implementation. In contrast to the EU Commission and the Council, the regulations are to apply uniformly throughout the internal market. A special liability regime for injured parties creates additional uncertainty: the substantiation of the damage and the causal contribution of a company should be sufficient to initiate legal proceedings. On this basis, companies are likely to find it difficult in many cases to exempt themselves from liability.

The vote in plenary is scheduled for the beginning of June. This will be followed by the trialogue with the Council and the Commission. The final text is to be agreed by the end of 2023, at the latest before the next EU parliamentary elections in May 2024.

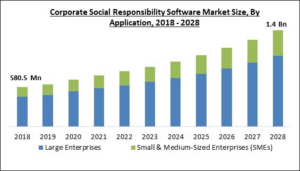

Source: © ResearchAndMarkets.com, CSR Software Market Report 2023

CSR software is booming

The market research company Research And Markets expects the market for CSR software to grow rapidly. By 2028, global sales of corresponding applications are expected to grow to 1.4 billion euros. At the same time, the proportion of SME users is growing. Where laws are not clearly formulated, large companies play it safe. This is already evident in the German LkSG. Example of the complaints mechanism: The law obliges companies with 3,000 or more employees (2023) or more than 1,000 employees (2024) to address the most important target groups of the complaint procedure – i.e. target groups with a high risk of being affected with regard to violations of environmental or social standards – in their own business area and in the supply chain to reach. How this is to be done is left open by the law. In its handout, BAFA recommends, among other things, hotlines and technical solutions for the supply chain. Suppliers are confronted with the request to dock onto the complaints system of large customers. If you’re unlucky, you’ll get a different tool from each key account. The same applies to reporting and information obligations. This quickly leads to disproportionately high provision and administration costs for SMEs – even without any risks or even violations.

Other EU sustainability regulations at a glance

In addition to the CSDDD, the EU is working on other sustainability standards, information and reporting obligations. Some have already been introduced, others are in the works. These include regulations on deforestation, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the updates to REACH and RoHS (Restriction of certain Hazardous Substances).

EU regulation on deforestation

The EU regulation on deforestation aims to reduce the impact of the European market on deforestation and forest degradation worldwide. The regulation obliges companies to prove that no forest has been cleared for the production of certain agricultural, animal and timber products after December 2020. Affected are palm oil, animals / goods of animal origin, soy, coffee, cocoa, wood and rubber as well as products made from them (= “relevant products”) that are to be sold on the EU market or exported from the EU to other countries. Annex I of the regulation lists the relevant products. For example, raw and tanned leather are also affected in the animals category and various wooden products such as wooden furniture, paper and cardboard in the wood category. Cellulose-based fibers are not (yet) on the list. However, there is no real all-clear: There have already been bad experiences at the national level with the EU Timber Regulation: The federal authorities have interpreted the product lists specified by Brussels very freely. Instead of the regulation on paper and cardboard ex chap. 47 and 48 of the Customs Tariff, the application was extended to paper and cardboard products. To this day, fines are imposed if, for example, labels are imported – separately from foreign-made clothing to which they belong – without an FSC seal.

Large retailers in Germany and the EU already require certificates such as FSC or PEFC for textiles made of cellulose-based materials (viscose, lyocell). The regulation is to be reviewed after only two years to determine whether further products should be included in Annex I. The regulation is expected to enter into force in the first half of the year. The rules will apply for 18 months after entry into force for large and medium-sized enterprises and 24 months for micro and small enterprises (balance sheet total up to a maximum of EUR 4,000,000, turnover up to a maximum of EUR 8,000,000, number of employees max. 50).

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)

The CSRD requires large companies to disclose non-financial and diversity information, including environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. It aims to improve the transparency and comparability of sustainability data and is designed to help investors, consumers and policymakers make informed decisions based on transparent sustainability information. To comply with the CSRD, companies must prepare a non-financial statement as part of their annual report that includes information about their ESG policies, risks, and performance. In addition to large companies, the CSRD also affects listed SMEs. Reporting must be based on European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). The CSRD also formulates reliability requirements for sustainability information and refers to the CSDDD that has yet to be adopted.

Updates to REACH and RoHS in 2023

The EU has updated the regulations on the chemicals regulation REACH and on Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS)) in 2023. The main changes are the inclusion of new substances in the list of substances of very high concern (SVHC) under REACH, the extension of the scope of RoHS to all electrical and electronic equipment (with exceptions), and revised thresholds for restricted substances under RoHS. To ensure compliance, companies need to regularly review updated lists and adjust their processes accordingly.

The Digital Product Passport (DPP)

The idea of the DPP is based on the European Green Deal and the Circular Economy Action Plan of the European Union. In March 2022, the EU Commission published the announced package of measures for its “Sustainable Product Initiative (SPI)”. The SPI is intended to ensure that more environmentally friendly products are approved and placed on the market on the European internal market in the future. As part of the proposed General Ecodesign Regulation, a DPP is to be introduced, which will store information on the physical composition and nature of products and share it along the industrial value chain. Among other things, the digital product passport should contain information such as where the product comes from, how it is assembled, how it can be repaired and dismantled, and how it is to be treated at the end of its service life. A key element of the DPP is the standardised exchange of data, which can also be accessed by waste disposal companies and retailers as well as public authorities.

Conclusions

The various sustainability legislations are likely to cause a surge in costs that medium-sized companies will find much more difficult to withstand than larger companies. Variety and small batch sizes can hardly be mapped anymore. The avalanche of bureaucracy will lead to less competition and more monotony in the market. In addition to accelerating the exodus of locations, a high risk is the disadvantage of suppliers in developing countries, who are likely to turn to customers in other countries. In addition to software providers, law firms, sealers, warning associations and consulting firms are likely to be among the beneficiaries of the new legislation.